With whom did Carl Gustav Jung, psychiatrist and founder of analytical psychology, correspond? Over 32,000 letters, carbons, transcripts and copies from six decades are now described in the ETH Zurich University Archives database and can be searched for online.

Instead of dictating a letter, Carl Gustav Jung gives an interview in the library at his house in Küsnacht, 1955 (ETH Library, Image Archive, Com_L04-0084-0033)

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) taught at ETH Zurich as a private lecturer and adjunct professor of psychology from 1933-1941. This position prompted him to bequeath his academic papers, including his extensive letter holdings, to ETH Zurich for research purposes. Previously, an internal card index was the only finding aid available to access any particular correspondences.

Now, however, the names of the roughly 6,000 correspondents are visible online, organised in alphabetical order from Aaronson to Zwingmann. As Ms Aaronson asked Jung for medical assistance, her letter is subject to a protection period. Zwingmann, on the other hand, whose correspondence is accessible without any restrictions, wanted to discuss nostalgia with Jung. A topic that did not interest Jung.

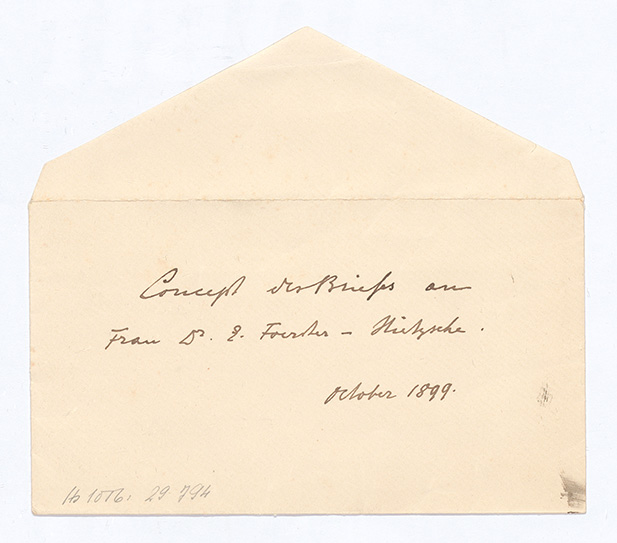

Envelope “Concept of the letter to Dr E. Foerster-Nietzsche, October 1899”; (ETH Library, ETH Zurich University Archives, Hs 1056:29794). © Stiftung der Werke von C.G. Jung, Zurich.

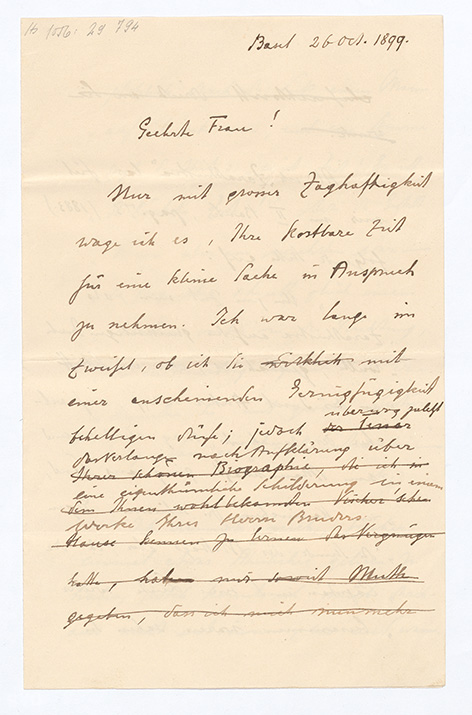

The oldest document in the correspondence holdings is a handwritten draft of a letter by Jung dated October 1899 to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, the sister of philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. The 24-year-old Jung was still studying medicine at the University of Basel at the time. Nietzsche had been a professor of classical philology there from 1869-1879 but, for health reasons, had taken early retirement and spent the next few years as a freelance philosopher until the onset of his mental illness. From 1897 he had been living in Weimar, mentally deranged, in his sister’s care, who also managed his work.

Jung had begun to delve into the books by the erstwhile Basel professor and was fascinated by Thus Spoke Zarathustra. When a section seemed strangely familiar to him, he turned to Nietzsche’s sister:

“Dear Madam!

It is only with great diffidence that I dare encroach on your precious time for such a trifling matter. I was long dubious as to whether I might trouble you with such an ostensible triviality; however, the urge for enlightenment regarding a peculiar account in one of your brother’s works ultimately prevailed. […]”

C.G. Jung to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, 26 October 1899, beginning (ETH Library, ETH Zurich University Archives, Hs 1056:29794). © Stiftung der Werke von C.G. Jung, Zurich.

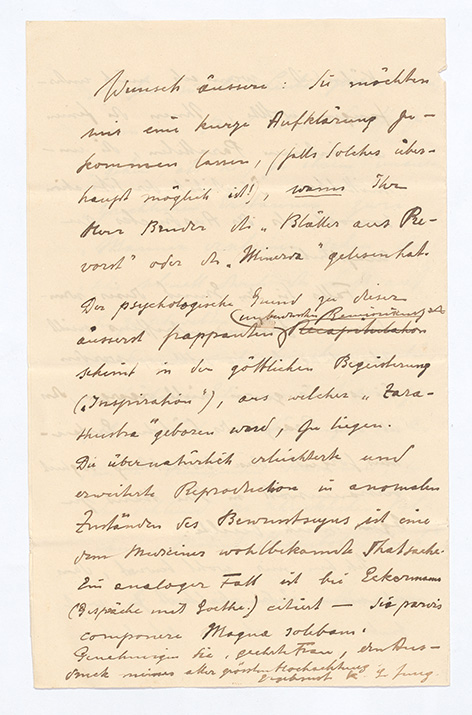

The well-read medical student had spotted a striking stylistic and content-related similarity with a ghost story from the magazine Minerva, which had been reprinted in Blätter aus Prevorst, a collection of accounts of strange episodes. Following pages of extensive quotations and precise references of the sections in question, he continued:

“[…] It would be far too audacious of me if I were to recapitulate the fine and intimate parallels, the direct identity of the situation and the expression.

In case you have not long known the reason for this wondrous encounter, surely you will not hold it against me that I, following my utmost astonishment, immediately hurried to offer you this observation.

I am well aware that I am going too far with my intrusiveness when I express my fond wish: would you be so kind as to explain (if this is even possible!) when your brother read Blätter aus Prevorst or Minerva?

The psychological reason behind this extremely astounding, unwitting reminiscence seems to lie in the divine relationship (“inspiration”) out of which Zarathustra was born.

The supernaturally facilitated and extended reproduction in abnormal states of consciousness is a fact that the physician is familiar with. An analogous case is cited in Eckermann (‘Gespräche mit Goethe’’) – Sic parvis componere Magna solebam [so I used to compare great things with small. Quote from Vergil, Eclogae 1].

Please accept, Dear Madam, the expression of my utmost respect.

Sincerely K.G. Jung”

C.G. Jung to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, 26 October 1899, end (ETH Library, ETH Zurich University Archives, Hs 1056:29794). ©Stiftung der Werke von C.G. Jung, Zurich.

The addressee presumably took a fairly dim view of the inflated epistle. For some time, accusations of plagiarism surrounding Nietzsche had been circulating. And now these new, embarrassingly accurate comparisons! She must have asked herself who this Jung was. Should she have known him? He had written from Basel, where a childhood friend and acquaintance of her brother’s lived and from whom she had distanced herself. Was someone now trying to set a trap for her?

But Jung had no intention of harming Nietzsche’s reputation, whom he greatly admired. He really was interested in the medical aspects of his discovery. In his 1902 dissertation Zur Psychologie und Pathologie sogenannter occulter Phänomene (On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena), he mentions written confirmation from Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche that her brother had read Blätter aus Prevorst at his grandfather’s house aged between 12 and 15, but not after that. It was then Jung himself who explicitly ruled out deliberate plagiarism on the part of Nietzsche.

In the archive database, the index of correspondences with other well-known and also unknown figures also includes all letters that were published in 1973 in the three-volume special edition of C.G. Jung’s letters and the collection of letters published in 1974 which he exchanged with Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis and Jung’s teacher; or the exchange of letters with Wolfgang Pauli, an ETH-Zurich professor and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics, which were published in 1992.

Anyone who, despite the rich range on offer, is unable to find what they are looking for should contact the ETH Zurich University Archives. After all, many letters from and to Jung are located in other holdings than his personal papers.

References

Quotations of Jung’s drafted letter to Förster-Nietzsche and images: courtesy of the Foundation for the Works of C.G. Jung / Stiftung der Werke von C.G. Jung, Zurich.

Bishop, Paul: The Jung/Förster-Nietzsche Correspondence, in: German Life and Letters 46 (1993), pp. 319-330. Containing the fully reprinted clean copy of C.G. Jung’s letter to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche from 26 October 1899, a draft of the Elisabeth Förster Nietzsche’s response to C.G. Jung from 24 November 1899 and another letter from C.G. Jung to Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche from 11. December 1899. All three are located in the Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv der Klassik Stiftung Weimar.

Liebscher, Martin: Libido und Wille zur Macht. C.G. Jungs Auseinandersetzung mit Nietzsche, Basel 2012, pp. 40-44.