From the 2nd of February to the 9th of March 1952, the travelling exhibition “Frank Lloyd Wright – Sixty Years of Living Architecture” made a guest appearance at the Zurich Kunsthaus. The reportage by Comet Photo AG (Zurich) immortalises in eighteen shots the obvious joy of discovery that the huge, almost overwhelming architectural models triggered in the public. Today’s viewers of this historical photo series will not fail to notice the contrast between the avant-garde appearance of Wright’s buildings and the out-of-fashion clothing of the museum visitors. However, if one takes clothing seriously as a cultural medium – and not as an anecdotal addition to the “actual” image content – it is precisely fashion that offers itself here as a common denominator between architecture, photography or photojournalism and personal image cultivation. The relationship between modernism, which from the beginning aimed at a comprehensive reform of life, even a permanent revolution along the lines of the technical-scientific innovation process, and fashion has always been fraught with tension and marked by contradictions. Such image sources as those of the Wright exhibition in Zurich in 1952 are irreplaceable for examining the history of architectural reception.

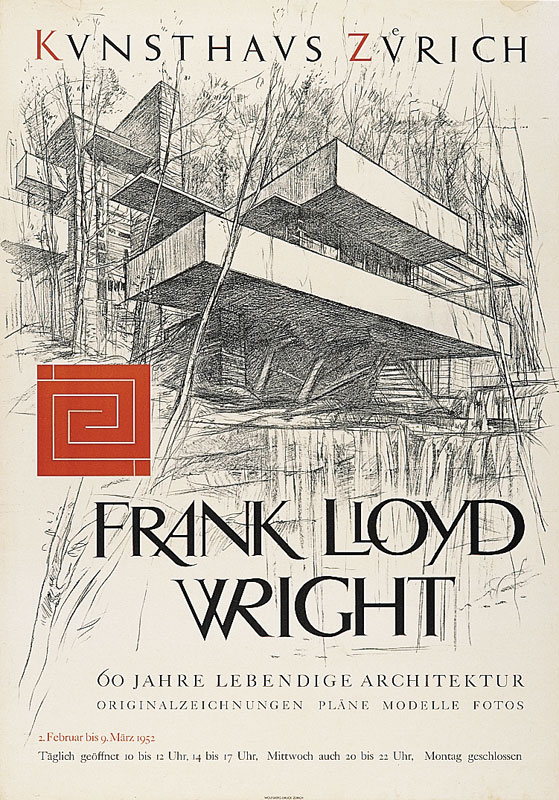

Exhibition poster by Walter Roshardt, Zurich. This poster, with adapted lettering, also announced the following exhibitions in Paris, Ecole nationale des Beaux-Arts, in April and in Munich, Haus der Kunst, in May 1952 (image from poster-auctioneer.com).

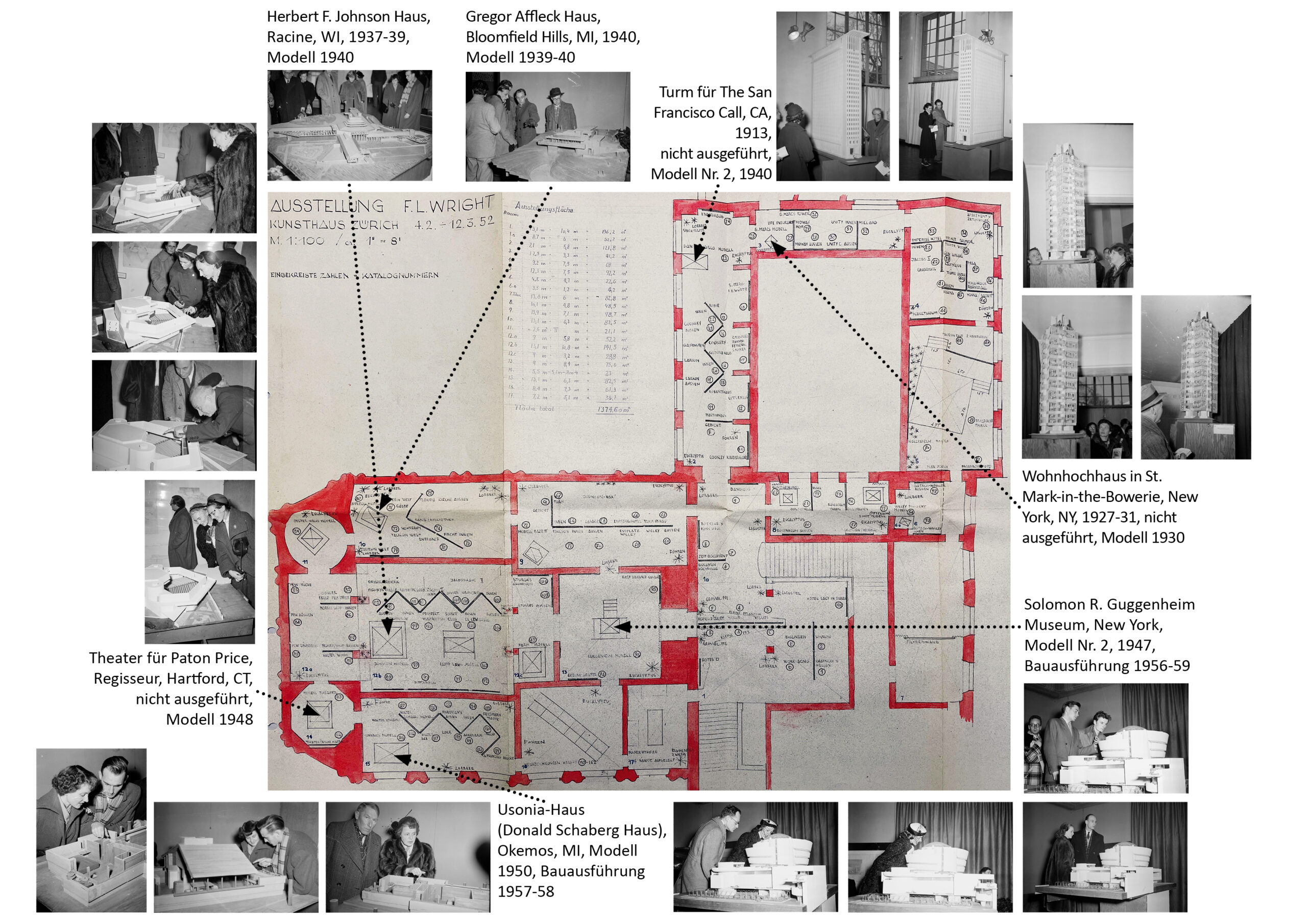

Spatial arrangement of the exhibition F. L. Wright at the Kunsthaus Zurich 1952 with locations of the photographs taken by Comet Photo AG (Zurich). (GTA archive, W. M. Moser estate; e-pics.ethz.ch; processing by the author).

The slow road of architecture to the general public

When reviewing the shots, one is struck by the constancy of the framing and thematic focus on the visual identity of anonymous visitors (physiognomy, clothing) and their personal confrontation with the models of Wright’s projects. No celebrities are brought to the fore. The Kunsthaus, an architectural setting deliberately chosen by the curators to lend a certain dignity to the exhibition, is not seen in any overall view and only appears very peripherally in the narrow frames. No model is photographed for its own sake, for its special architectural interest, its easy didactic disassembly or its contribution to a current issue in local politics. Nor has any other exhibit or communication medium (original Wright drawing, rear projection system) attracted the attention of the photojournalist. The theme of this series could thus be described as “Architecture and Community” or, better still in English, “Architecture – You and Me”, in reference to the collection of essays published in 1956 and translated in 1958 by Sigfried Giedion, the internationally renowned Zurich architectural historian and critic who had already made Wright known among his students at Harvard University and ETH Zurich in the late 1930s.

In these pictures it becomes clear that the focus is not on the architecture itself, but on its path from the professional world to the public. This path is not without obstacles: Some visitors express unease or scepticism, others a somewhat forced, theatrical admiration, still others compare their observations in visibly animated dialogues.

Queing in front of the podiums

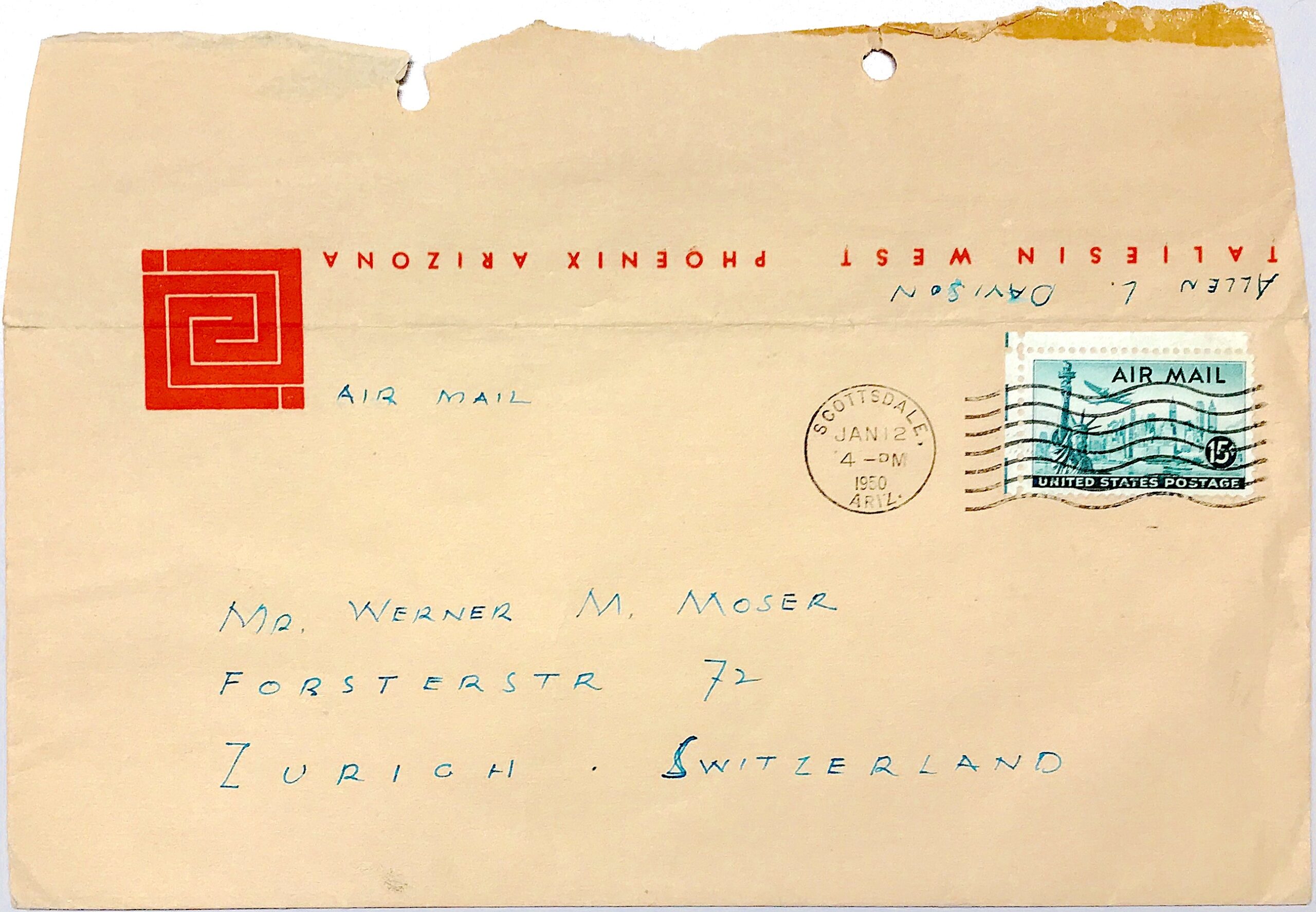

The architectural models were presented on plinths of different heights: The design of the residential tower for St-Mark-in-the-Bowerie, New York, for example, was placed at shoulder height so that visitors could enjoy the façade effect of the mill-wheel-wing-shaped ground plan and the complex section virtually from street level, while the Usonian House (Donald Schaberg House) was placed at elbow height so that the façades could be comfortably observed from the side and the room layout from above.

Model (1930) of the residential tower for St-Mark-in-the-Bowerie, New York, 1927-31 (not realised) (Com_M01-1270-0019).

Model (1950) with removable roof of a Usonian house later commissioned by Donald Schaberg and built in Okemos MI in 1957-58 (Com_M01-1270-0011).

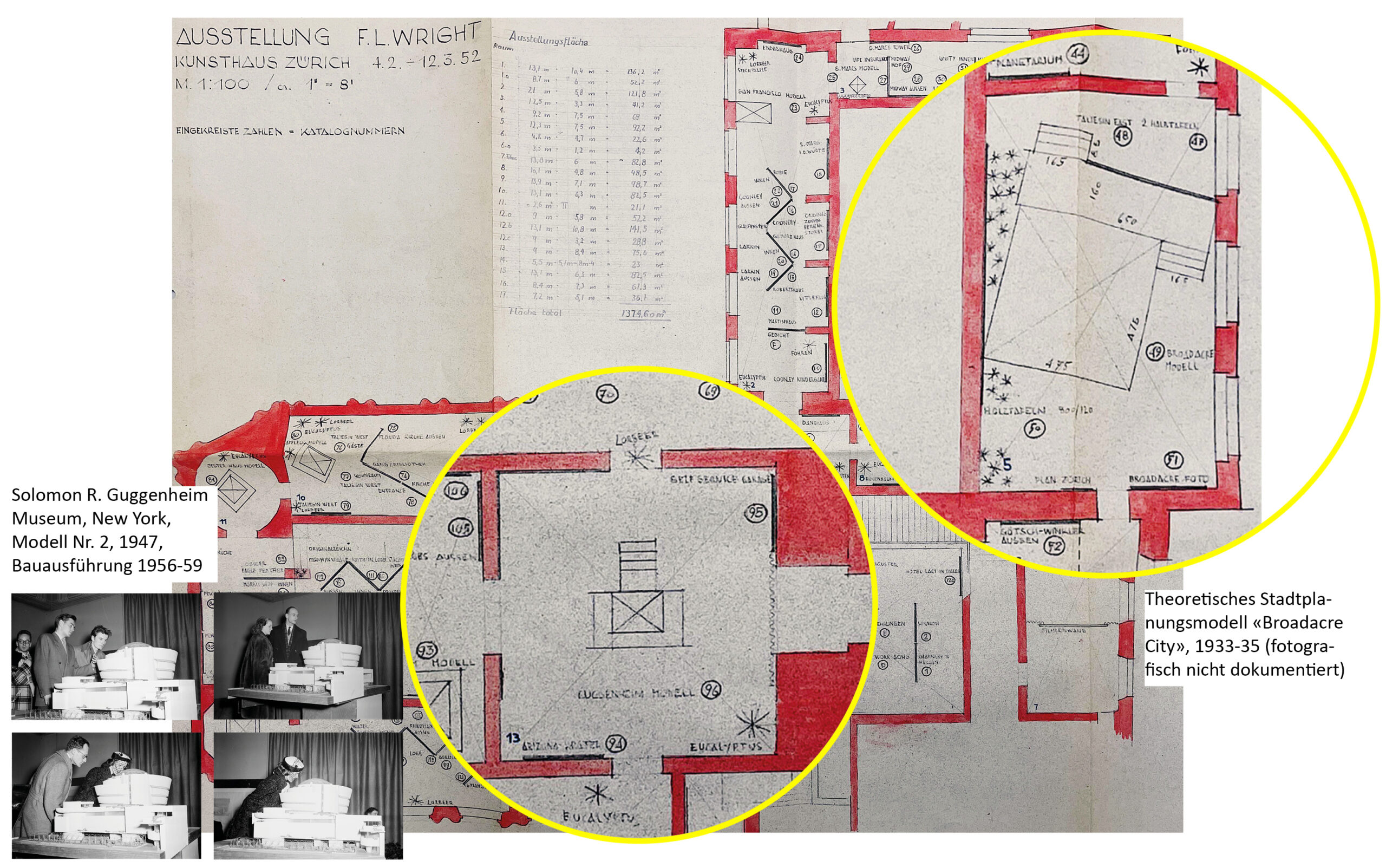

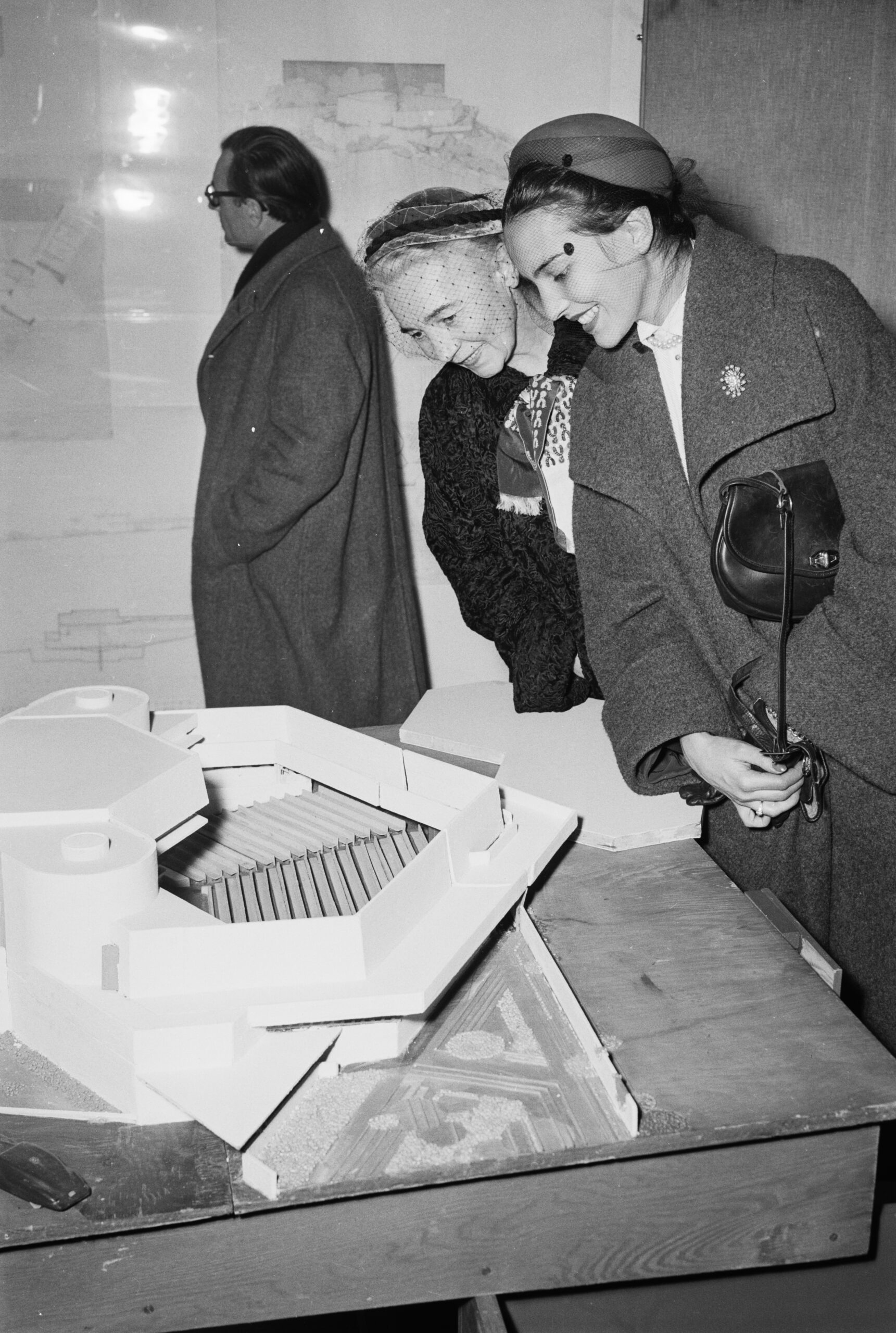

Two models benefited from a special staging that not only promoted the reading of the object, but at the same time exposed the visitors to the public’s gaze: the Guggenheim Museum in New York, whose model was raised onto a platform that could be reached via a narrow staircase; the urban planning model of Broadacre City, which could be viewed both from above via a catwalk on the side and up close from the edge of the table.

Details of the spatial arrangement of the exhibition highlighting the locations of the Guggenheim Museum model, left, and the photographically undocumented Broadacre City urban planning model, right (plan of the 1st floor in the GTA archive, Werner M. Moser estate, photos from e-pics.ethz.ch, editing by the author).

The fact that the Guggenheim Museum project and the above-mentioned apartment building models were photographed in three-four variations with different types of visitors (young people/adults, women/men, fashionably/conservatively dressed), while the Broadacre City urban planning model, although presented in a spectacular and unavoidable way, did not leave the slightest photographic trace, requires an explanation. Since news agencies operate on the principle of supply and demand, it can be assumed that the subject of urbanism was difficult to market to the general public in photojournalism. Moreover, probably none of the target audiences of the illustrated newspapers had the minimum level of competence to have access to one or the other forum where urban planning issues were debated, while all of them felt relatively safe when it came to taking a public position on architectural projects, even if only by admiring or rejecting them.

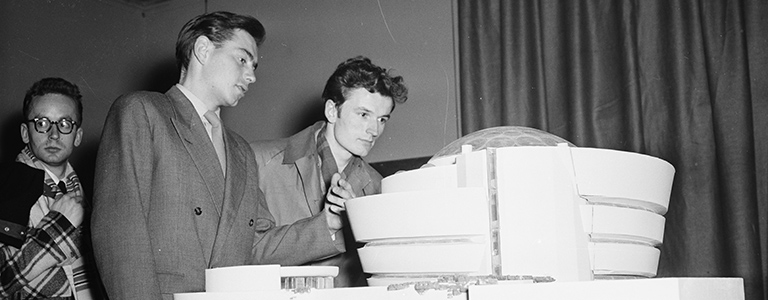

Four nearly identical views of the second model (1947) of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, with changing types of visitors (Com_M01-1270-0014).

Four nearly identical views of the second model (1947) of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, with changing types of visitors (Com_M01-1270-0003).

Four nearly identical views of the second model (1947) of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, with changing types of visitors (Com_M01-1270-0004).

The photo shows in the foreground the southern side façade of the planned museum, which at that time was still separated from 88th Street by a narrow plot of land. It was not until 1951 that this lot could be acquired and the project developed across the entire front of the block on 5th Avenue, facing Central Park, between 88th and 89th Streets. The cone-shaped rotunda was then moved from the northwest corner to the southwest corner of the lot. The photographed visitors enjoy looking at the main facades, which are then hidden from the readers of the reportage.

Architecture, publicity and fashion literally «brought under one hat»

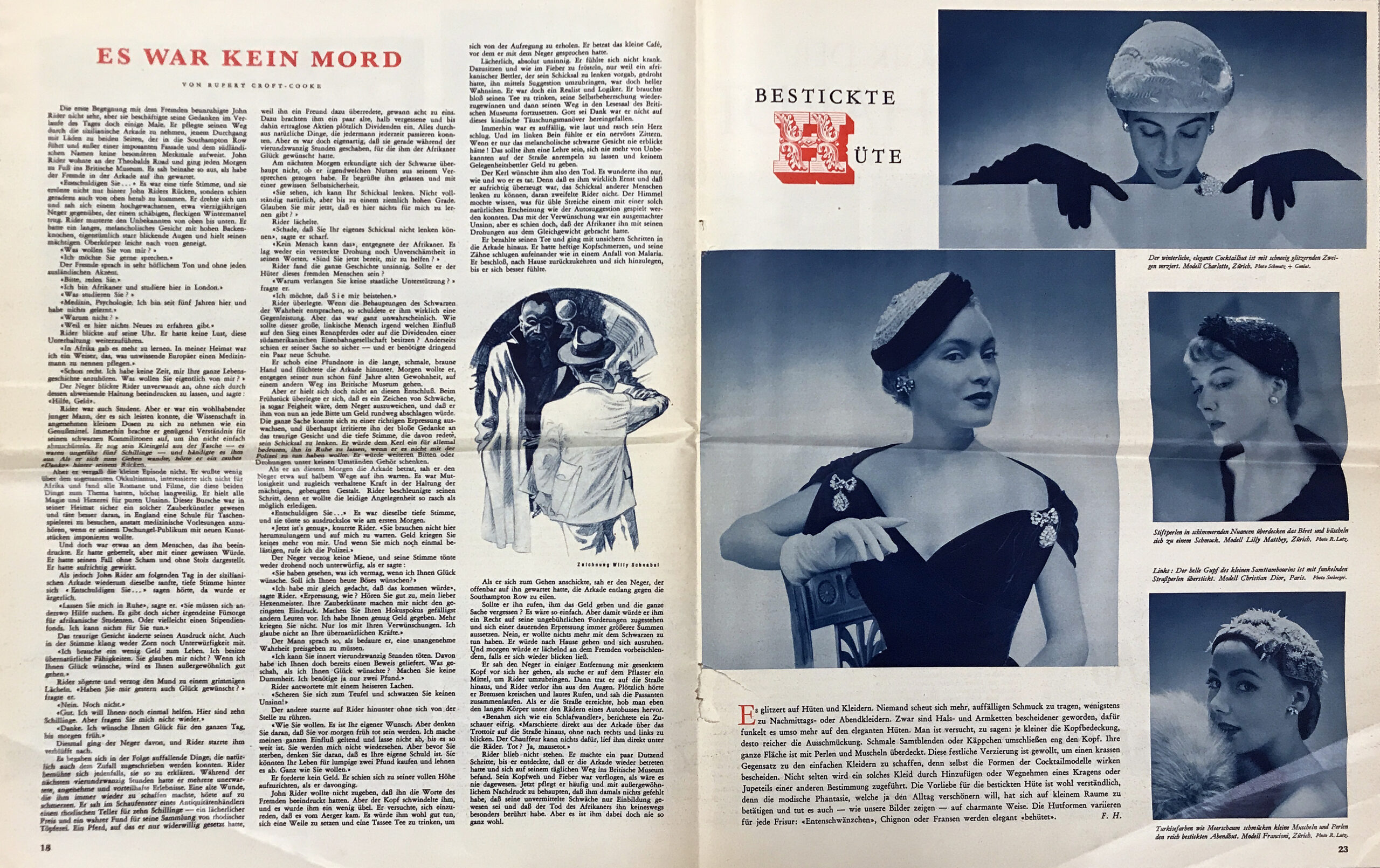

On January the 31st 1952, two days before the opening of the exhibition, Sigfried Giedion, who was so keen to bring architecture closer to the general public, published a two-page article in the illustrated magazine “Sie und Er” (Ringier Verlag) entitled “Frank Lloyd Wright, American and Individualist”. Against the backdrop of the Cold War, this succinct title sounds almost like a political slogan, but the report instead goes into detail about episodes from the architect’s turbulent life, his early success, his lean years and his late recognition. Behind this moral portrait is the impact of King Vidor’s 1949 film The Fountainhead, with Gary Cooper in the role of the uncompromising architect convinced of his civilising mission. If you turn the pages of the magazine, you will find a short story by the English writer Rupert Croft-Cooke (known in Switzerland as a lecturer at the Montana Zugerberg Institute) under the heading “It wasn’t murder”. This tale of a strange encounter near the British Museum between a coolly rational art historian and an African medical student who, in exchange for a modest donation, promises to influence his fate favourably with the help of his occult powers, is an accidental echo of Giedion’s invocation of American individualism. Indeed, it takes up in the form of a fable the old Aristotelian question of whether everyone is the architect of his own fortune or whether, on the contrary, our own fortune depends on our goodwill towards others. Five pages further on, a short, richly illustrated article comments on the fashion for “embroidered hats”, some of which look strikingly similar to the hats worn by many visitors to the exhibition. It also mentions the standard of appropriateness that makes these small hats socially acceptable: “The preference for the embroidered hats is well understandable, because the fashionable imagination, which wants to embellish everyday life, has to work in a small space (…)”. The images of Comet Photo AG thus merge content in a single image frame, which the magazine divides into different sections.

Illustrated magazine “Sie und Er”, 31 January 1952 (GTA Archive, Sigfried Giedion estate)

Exhibition visitors with newfangled hats consider the theatre project for director Paton Price, Hartford, CT, not realised, model 1948 (Com_M01-1270-0012)

Once architecture is no longer confined to its professional environment and begins to address the general public, the arguments for its judgement are no longer derived from the study of the buildings themselves, but more generally from the relationships they enter into with individual and collective lifestyles (those of the author, his clients and the society to which they belong). The technical-artistic know-how retreats (temporarily) so that the ethical criteria can determine the debate. Is the US way of life worthy of influencing the modernisation of our living conditions on this side of the Atlantic? Does it offer the prospect of a better and happier life? What traits of Frank Lloyd Wright command respect and make us side with him (or just not)? Did he have the temperament of an explorer, did he expand our knowledge, sharpen our sensibility, increase our freedom? Was he courageous, generous, did he strive for the common good of the “polis” and for excellence in all things, as he claimed in his often self-aggrandising publications?

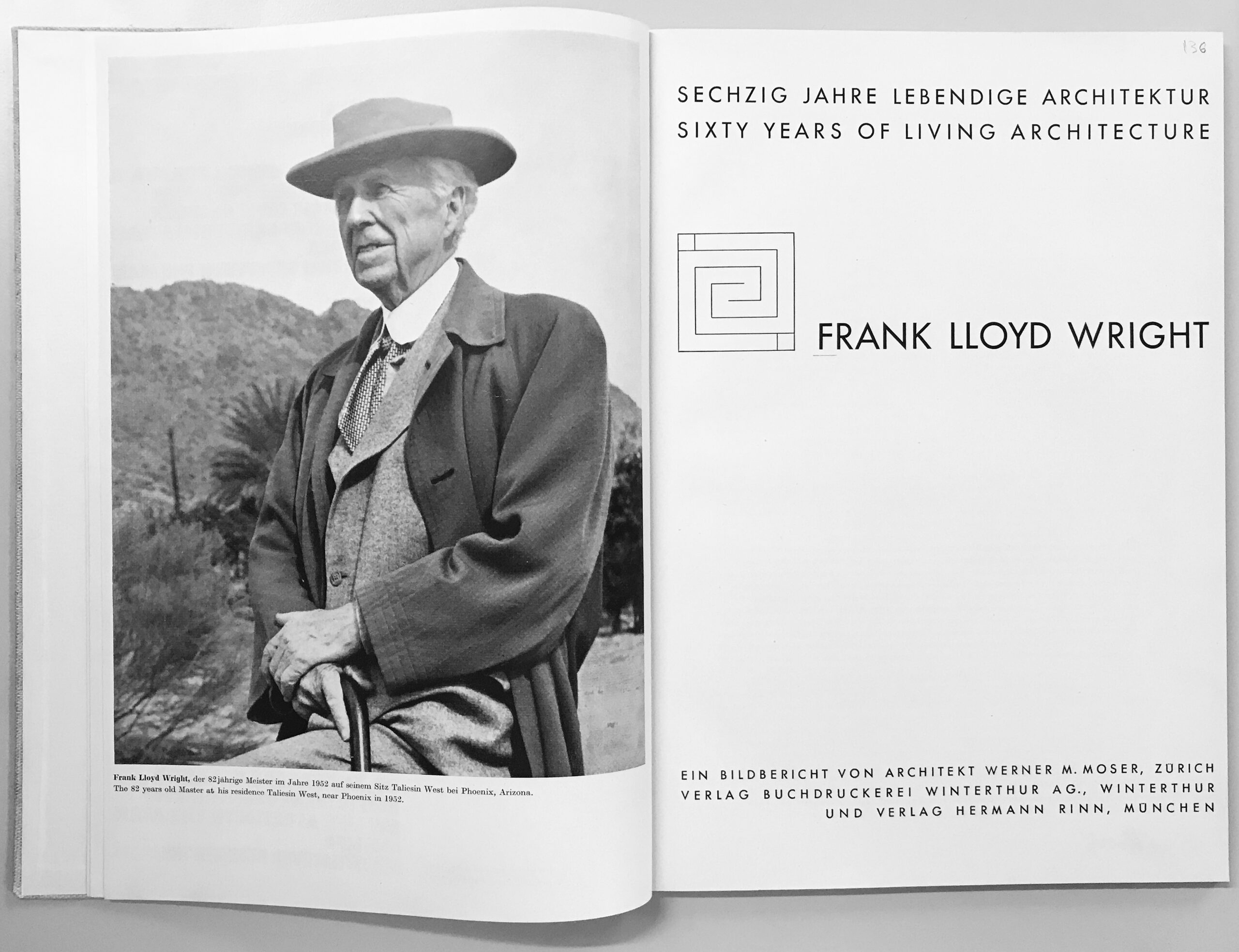

Wright obviously had a sure judgement in all sorts of areas with which he could carry away his interlocutors, starting with his very personal choice of clothes, which gave him style without conforming to the latest fashion.

Frontispiece with Wright’s portrait and title page from Werner M. Moser: Frank Lloyd Wright – sechzig Jahre lebendige Architektur / Sixty years of living architecture: ein Bildbericht. Winterthur: Verlag Buchdruckerei Winterthur, 1952. – The caption contains an error regarding the age or date of the photograph: either Wright was eighty-four years old at the time or the photograph was taken in 1950.

Wright’s style of dress: an elegance adapted to the great outdoors, far removed from the conformism and consumerism of the big cities.

In urban planning, Wright resolutely favoured the construction of single-family homes organised in diffuse urban structures that placed a high value on the natural environment. This commitment to anti-urban individualism was bound to lead him to reject the obligatory standards of dress in the business world and the ephemeral fashions to which the populations crammed into large cities resorted in order to individualise themselves and identify their groups of belonging. This does not mean, however, that Wright wanted to renounce all elegance and encouraged the inhabitants of his houses to dress like farmers, lumberjacks or prospectors. In his opinion, clothing should express not only the personality of the wearer but also a vision of man as a seeker of happiness, striving for authenticity and in close contact with nature.

Wright ensured that the best press photographers, including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Alfred Eisenstaedt, Arnold Newman, Yousuf Karsh, Richard Avedon, Berenice Abbott and Pedro Guerrero, documented his style of dress, which he maintained with a constancy that was impossible to confuse with mere fashion. These photos, widely circulated by the mass media (Life, Newsweek, Harper’s Bazar, Vogue…), eventually gave him iconic status.

The felt Pork Pie hat became such a typical Wright attribute that it was remade in a limited edition to celebrate the architect’s 150th birthday. The wide-brimmed hat not only protected him from rain and the sun’s heat, but in combination with the good shepherd’s stick and the raglan coat it also recalled the silhouette of the Quaker field preachers, whose freedom of thought and moral rigour he admired. Whether he was in the hills of Wisconsin, in the Arizona desert or in New York at a press conference, these accessories never left him. His three-piece suits were tailored from the tweed common to English sportswear, with the jacket cut straight or crossed. The light shades openly contested the need to dress in black, which had become an unspoken rule of bourgeois society, as if to be elegant one had to mourn someone or something. He was a master at combining starched collars with silk banderos whose ends fluttered freely. In today’s terminology, Wright’s style would be described as sporty-chic with a touch of exoticism and artistic pride.

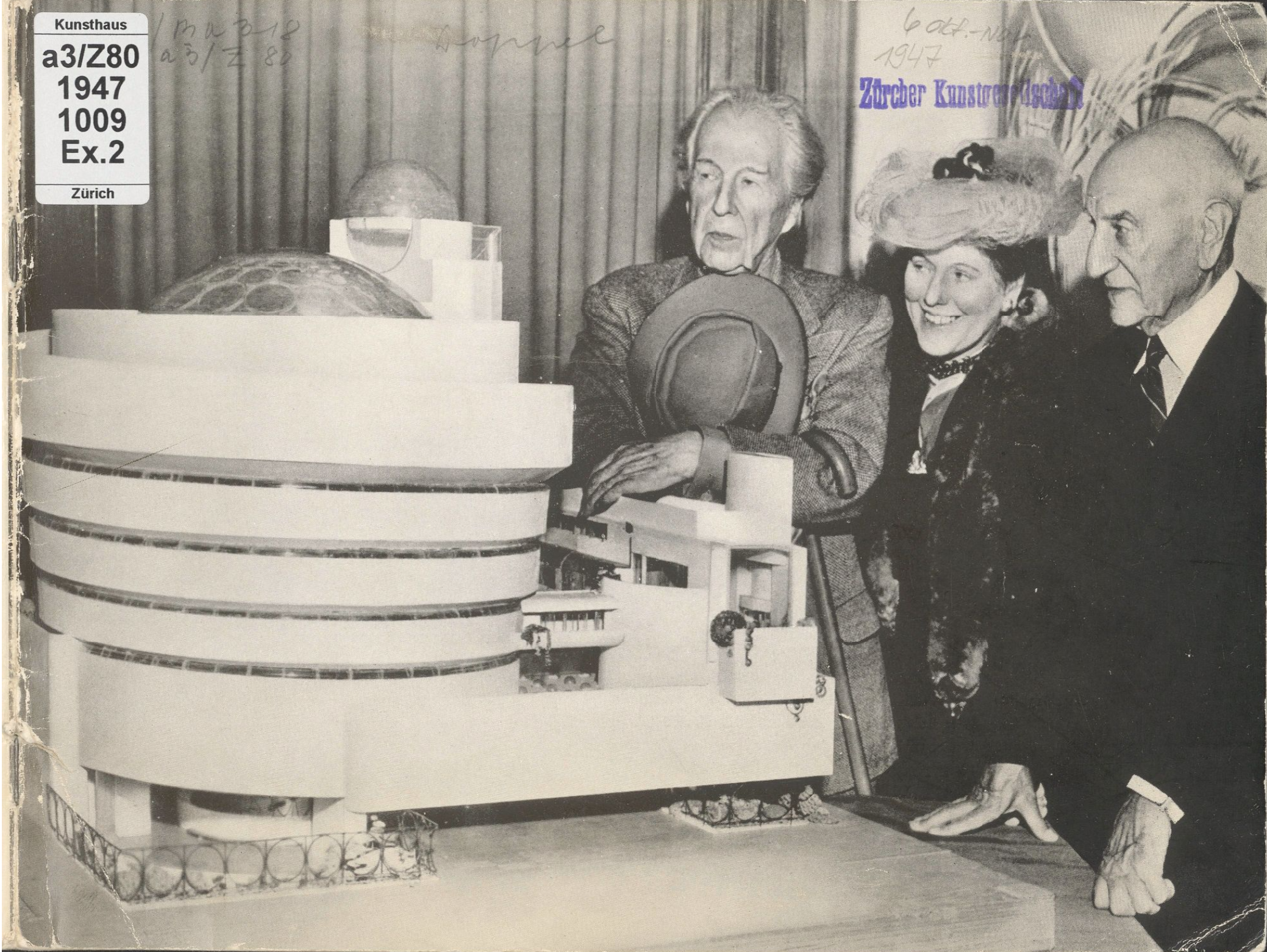

First public presentation of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Project in New York in 1945. F. L. Wright is accompanied by the artist, gallerist and initiator of the project Hilla Rebay von Ehrenwiesen and the founder. Cover of the accompanying publication to the exhibition “Zeitgenössische Kunst und Kunstpflege in den U. S. A.”, which was shown at the Kunsthaus Zürich in autumn 1947. The photo shows Model No. 1 from 1943-45 (https://digital.kunsthaus.ch/viewer/fullscreen/44322/1/).

The two plans for the New York project and the third extension of the Kunsthaus in Zurich, designed by Hans and Kurt Pfister, began in the same year, 1943, and were opened in Zurich in 1958 and in New York in 1959. During this decade and a half, information about the development of the Guggenheim project was constantly disseminated in Zurich, not only to stimulate local debate but also to secure international support in New York.

Consensus and dissent translated into dress codes

It is not only the opposing pair of urban sociability/anti-urban individualism that knows forms of translation both in spatial design and in the clothing of the population. The reportage by Comet Photo (Zurich) also testifies to the clash of divergent positions in the museum space, which can be located on the axis of official culture/ protest culture.

In the early 1950s, however, it seemed that the Kunsthaus as a privileged site of cultural debate was not fundamentally questioned, not even by those who assigned themselves to the subcultures. Just as everyone agreed that the relatively severe winter of February 1952 (average temperature in Zurich -1.4°) called for warm clothing, and that the genre of “winter clothing” was only differentiated into the sub-types “fur”, “woollen coat” and the entire range of mackintoshes in a second step, everyone also largely agreed that this prestigious travelling exhibition, which stopped off in Zurich after Philadelphia and Florence and before Paris, Munich, Rotterdam, Mexico City and New York, was to be received in the Kunsthaus, the most dignified setting the city had to offer, and that it therefore required appropriate but not exactly festive clothing, which could later be varied with a touch of individuality.

View of the second model (1947) of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York with three visitors who, for the occasion, have adapted their clothing to the undisputed dignity of the place, each in his own way (Com_M01-1270-0008).

In one particularly telling photograph, three young men, probably architecture students, are seen wearing contrasting styles of clothing in the same frame. The crossed jacket in the foreground is a little too loose (ready-to-wear clothing became more common in the second post-war period), but shows a preference for the classic look, which is impeccable but also risks being interchangeable; The young man on the right wears a raglan mackintosh with sophisticated waterproof seams over a bright jacket that approximates the Wrightian trend, while the third boy with a three-day beard on the left wears a Pendleton tartan jacket that overtly connotes his Anglo-Americanophilia and places him between the jazz-loving Zazous of the 1940s and the more literary Beat Generation of the 1950s.

When reality is caught up with fiction.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Martin Scorsese’s staging of the fashion creations of couturier Charles James (1906-1978) in the Frank Lloyd Wright Room on the occasion of the exhibition “In America: An Anthology of Fashion”, 7 May – 5 September 2022. (Anna-Marie Kellen / © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, from ADPRO, website)

The Architectural History and Fashion History departments of the Metropolitan Museum of Art have been exploring the heuristic potential of hybridising their respective collections and exhibition spaces for three years. This year (summer 2022), twelve film directors were invited to stage an “Anthology of North American Fashion” in the Met’s famous period rooms. Martin Scorsese got involved in the game of installing the dresses and suits of fashion designer Charles James in the former salon (transferred to the museum since 1972) of the mansion built by F. L. Wright for Francis W. Little in Wayzata, MN, in 1912-14. The confluence of the costumes and the architectural setting unleashes a fictional evocativeness that Scorsese was able to exploit brilliantly. Film buffs will probably recognise a similar atmosphere to John M. Stahl’s 1945 film “Leave her to Heaven”, which – apart from Gene Tierney’s mesmerising look – went down in film history as the first film noir in Technicolor.

Model (1939-40) of the Gregory Affleck House, Bloomfield Hills, MI, 1940 (Com_M01-1270-0007)

Our photo collection offers room for similar interference if it should turn out that the person seen from behind in the picture above at the left edge is Max Frisch, who finally exchanged the architect’s pencil for the playwright and novelist’s pen in 1955. Moreover, the codes of American film noir subtly tempt us to recognise in the figure with the soft fedora a private detective disguised as an ordinary citizen who pretends to be interested in modern architecture in order to be able to pursue a suspect more inconspicuously, and to catch just the slightly too casual guy in his polo coat with the collar up to be up to something evil. If you forget to take off your gloves when visiting a museum, especially if they are made of thick leather, you inevitably give away amateur theft…

On the prehistory of one of the most ambitious and diplomatically complex international cultural events of the post-war period

The circumstances surrounding Frank Lloyd Wright’s acceptance in 1949 of a joint invitation from humanities scholar Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti and his fellow Harvard Graduate School of Design graduate Bruno Zevi – both political activists in post-fascist Italy – to mount a retrospective of his work in Florence have been extensively researched and published (see bibliography below). The repair of wartime damage in Florence was the focus of intense controversy, and the exhibition’s curators hoped that greater familiarity with Wright’s work would encourage the elaboration of a creative solution rather than a simple “dov’era com’era” reconstruction (see https://etheritage.ulapiluh.myhostpoint.ch/2022/06/17/florenz-zertruemmertes-herz/).

The need to give the Florence exhibition the form of a travelling exhibition, involving the foreign departments of several governments against the backdrop of the Cold War, arose only after the main sponsor in the USA, Arthur C. Kaufmann (cousin of the client of the famous Fallingwater house), declared that he would not cover the costs of sea transport to Europe. A. C. Kaufmann suggested that the German-born architect Oskar Stonorov, who had emigrated to the USA in 1929, be entrusted with the overall coordination. The latter was actually the right man for the job, because he felt at home both in Florence, where he had begun his architectural studies in 1924, and in Zurich, where he had completed them with Karl Moser at the ETH, and in Paris. There, in the famous studio in the Rue de Sèvres, together with Willy Boesiger, he had compiled the material for the first volume of Le Corbusier’s collected works, which was published by the Girsberger publishing house in Zurich in 1930.

Florence, overview of the Ponte Vecchio and the bridgehead on the right bank destroyed in 1944, c. 1950 (Com_M01-0717-0005)

Florence, Palazzo Vecchio (Fel_054975-RE)

The preview of the exhibition took place in Philadelphia in January/February 1951 at the Gimbel Brothers Department Store, of which A. C. Kaufmann was the CEO, and attracted almost a hundred thousand visitors. The European tour opened in Florence on the 24th of June 1951 in the presence of Wright, who was led in triumphal procession to the sound of silver trumpets from the Palazzo Vecchio, where he was made an honorary citizen, to Leon Battista Alberti’s iconic Palazzo Strozzi, the home of the exhibition. After two months, the number of visitors (twenty-five thousand, after all) did not meet the expectations of the Italian initiators, who decided, without consulting Wright and Stonorov, to make a next stop at the Milan Triennale and use the remaining time to prepare the temporarily confiscated corpus of Wright’s drawings for publication in book form. Naturally, this led to an éclat with the other curators, who had long since fixed their exhibition programmes for 1952 and could not be satisfied with an exhibition shortened by essential parts. After Stonorov had put the tour schedule back in order, the eight freight crates set off for Zurich, then Paris (Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux arts, curator Darthea Speyer), Munich (Haus der Kunst, curators Brigitte d’Ortschy and Otto Bartning) and Rotterdam (Ahoy Hall, in collaboration with J.J.P. Oud) before being transported back to New York with a diversion via Mexico City.

Werner Max Moser, curator of the exhibition in Zurich

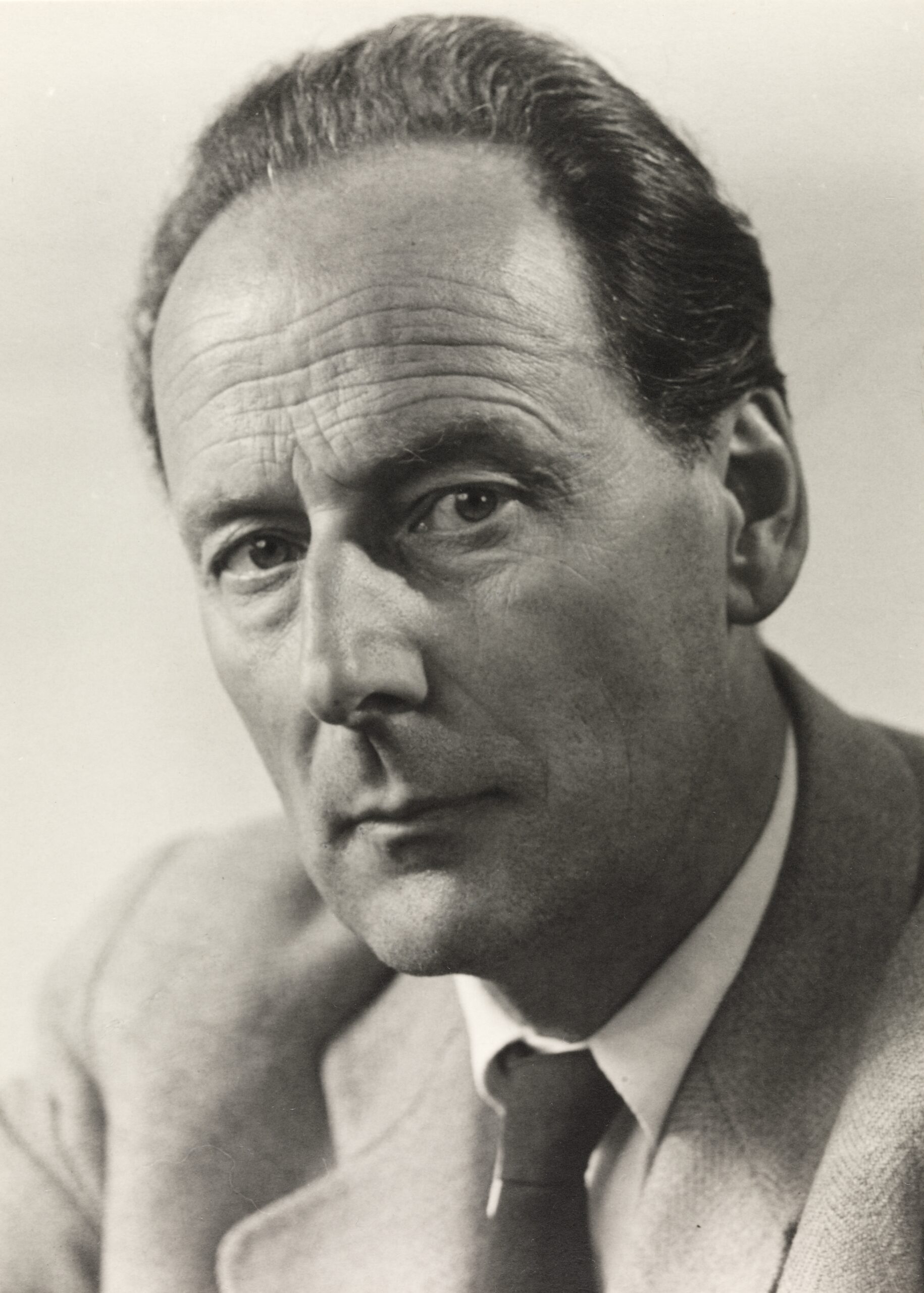

In contrast to Bruno Zevi, who had become acquainted with Wright in 1938/39 through Sigfried Giedion’s Charles Eliot Norton lectures at the GSD in Harvard, Werner Max Moser, as a newly graduated architect, had gained his first professional experience with Frank Lloyd Wright in the USA in the early 1920s and formed a lasting friendship with him.

Werner Max Moser, curator of the Wright exhibition in Zurich 1952, portrait by Ilse Reinhard, 1949 (Portr_01663)

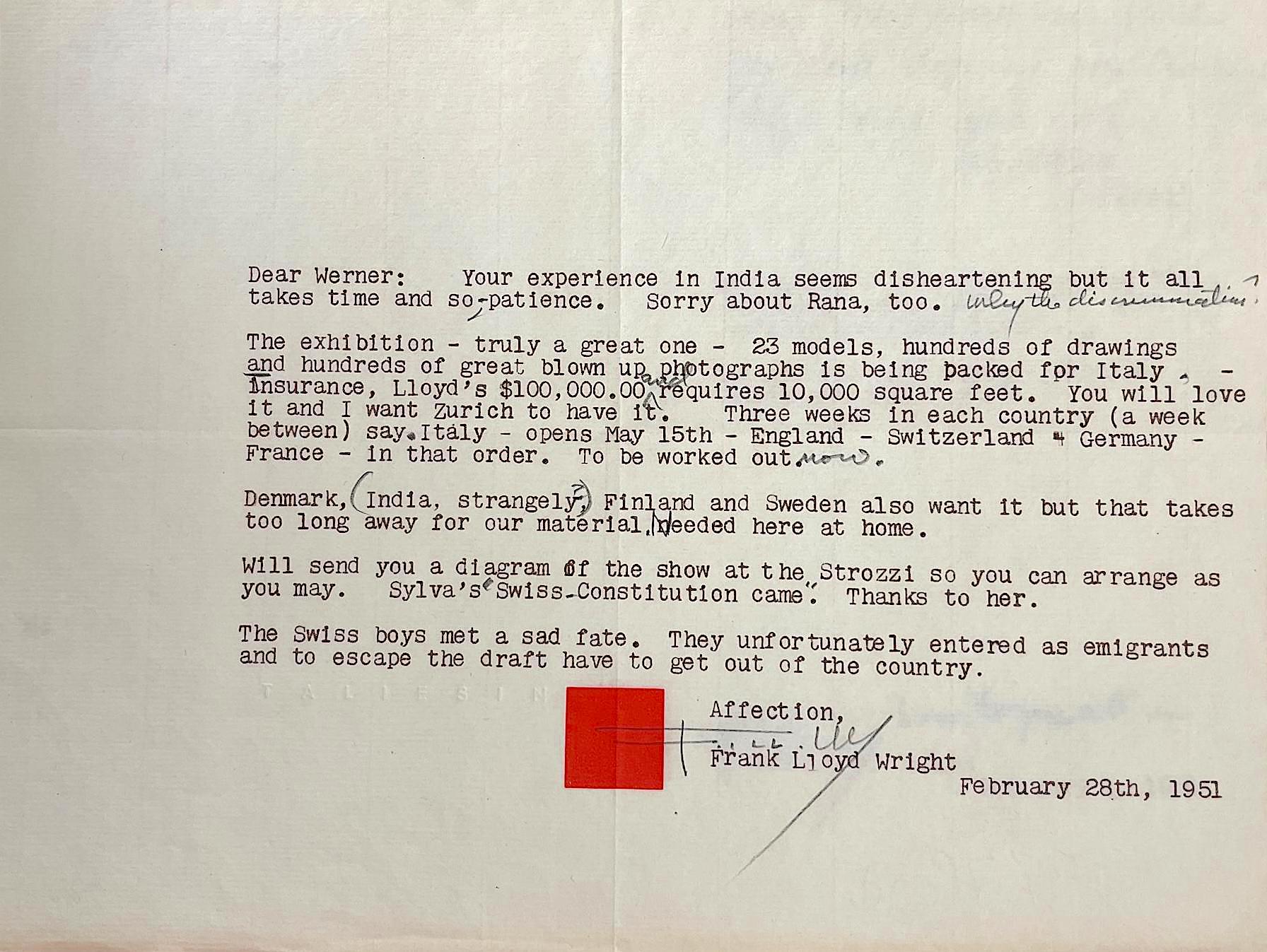

Pieces of correspondence from Frank Lloyd Wright and his assistant Allen Lape Davison to Werner Moser on the office stationery designed by the architect (GTA Archive, ETHZ).

Kunsthaus versus Museum of Applied Arts

In the preparatory phase for hosting the exhibition in Zurich, Moser contacted the master by letter on the 18th of May 1951 to determine a suitable location: “I consider the Artmuseum – Kunsthaus Zurich: Director Wehrli – as a more dignified place, than the more technical exhibition hall in the “Kunstgewerbeschule” with Director Itten” (letter in Moser’s estate, gta archive; emphasis SM). The eighty-four-year-old, internationally recognised American architect deserved a worthy reception. Since the Italians had already set the bar very high by choosing Alberti’s Palazzo Strozzi as the exhibition venue, Moser had some reasons to doubt his ability to compete in the race with the austere and New Objectivity aesthetic of the Museum of Decorative Arts. The Art Nouveau building on Heimplatz was obviously the best that Zurich had to offer a distinguished guest of the calibre of F. L. Wright. The fact that the Kunsthaus had been built and extended by Karl, Werner Moser’s father, could possibly flatter the son, but did not change the fact that the noble setting of the Kunsthaus was more appropriate if Wright was to be publicly honoured for his life’s work.

In addition, the acquisition of the travelling exhibition was contingent on a private sponsorship of at least CHF 25,000 (in the value of the time). Donors would be more inclined to be generous if the organisation of the event promised a prestige gain. With the choice of the Kunsthaus as the exhibition venue, the prospects for sufficient financial resources were thus more favourable.

School of Applied Arts and Museum of Applied Arts of the City of Zurich, 1930-33, Adolf Steger and Karl Egender, architects, west façade, photo 1937 (Archiv ZHdK / emuseum.ch/search/aeb-2003-a02-213)

Kunsthaus am Heimplatz, Zurich, Karl Moser, architect, 1907-1910, second wing added 1924-26, photo Wilhelm Gallas, 1935 (https://baz.e-pics.ethz.ch/main/thumbnailview/qsr=BAZ_085316)

Kunsthaus am Heimplatz, Zurich, Karl Moser, architect, 1907-1910, second wing added 1924-26, photo Wilhelm Gallas, 1935 (https://baz.e-pics.ethz.ch/main/thumbnailview/qsr=BAZ_085316)

An exhibition of superlatives

“There never has been – they say – so complete an impressive architectural exhibit on earth heretofore”, Wright wrote with his typical modesty to his Zurich friend on the 4th of April 1951, after the latter had enquired about the volume, weight and insurance value of the exhibits. In fact, almost thirteen tons of exhibition material were shipped in eight freight crates from the port of Philadelphia to Genoa and from there transported through Europe in three freight cars. At the Kunsthaus Zürich, the 1400m2 of the upper floor was just enough to display the following exhibits:

- 47 double-sided panels on stands

- 26 panels for hanging

- 16 models including model stands

- 1 rear projection screen for an automatic slide show

- 1 bridge for the Broadacre town planning model so that visitors could view it from above

- 1 sound amplifier with loudspeaker for the transmission of Wright’s recorded lecture on this subject

- 8 exhibition tables with glass panels for the presentation of a selection of original drawings

- 6 large volumes of photographic reproductions of approximately 900 original drawings to be offered for consultation in cabinets.

At the end of this enumeration, Wright regretted that the full-size model of a Usonian house built for the preliminary presentation of the exhibition in Philadelphia was too large to send!

Between the 2nd of February and the 9th of March 1952, no less than 22,000 people visited the exhibition at the Kunsthaus Zürich, with the record number of 2,195 latecomers being reached at the last minute on the closing day of the event! Visitors literally pounced on the catalogue, 1300 copies of which were sold out a week before the end of the exhibition.

Model No. 2 (1940) of the head office of The San Francisco Call, 1913 (not built) (Com_M01-1270-0006).

Model (1930) of the residential tower for St-Mark-in-the-Bowerie, New York, 1927-31 (not built) (Com_M01-1270-0009).

The photo report shows the excellent reception of the catalogue written by Werner Moser, which also seems to have been appreciated by the professionals as a writing and drawing pad during the visit.

Bibliography and Webography

Exhibition poster:

- https://poster-auctioneer.com/en/realisierte_preise/view_real_price/Bosshard-Walter-Frank-Lloyd-Wright-299299 /

- http://permalink.snl.ch/bib/chccsa000007302)

Accompanying publications to the exhibition:

- Kunsthaus Zürich: Frank Lloyd Wright – 60 Jahre lebendige Architektur. Ausführliches Verzeichnis mit 6 Abbildungen, Zürich : Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1952. 40 S., Ill., 21 cm.

- Werner M. Moser: Frank Lloyd Wright – sechzig Jahre lebendige Architektur / Sixty years of living architecture: ein Bildbericht. Winterthur: Verlag Buchdruckerei Winterthur, 1952. 100 S.: Ill., z.T. farb. Textabb. & Plänen, 30 cm.

- Peter Meyer, Werner M. Moser, «Frank Lloyd Wright, Sechzig Jahre lebendige Architektur», Schweizerische Bauzeitung Jahrgang, Nummer 34, 23. August 1952, Seiten 479-487, online < https://www.e-periodica.ch/cntmng?pid=sbz-002:1952:70::453>

Source material for the station in Zurich of the travelling exhibition ” F. L. Wright – 60 Years Living Architecture “:

- 19 photographs online ETH-Bibliothek Zurich, Picture Archives / Photographer: Comet Photo AG (Zurich) / Com_M01-1270-0001 to Com_M01-1270-0019 / CC BY-SA 4.0

- ETH Zurich, Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Architektur, gta Archive, Stefano-Franscini-Platz 5, CH-8093 Zürich, bequests of Werner Max Moser and Sigfried Giedion.

- Kunsthaus Zurich, Library, Rämistrasse 45, 8001 Zürich

- Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, photography class, 8 photographs of models at the Wright exhibition at the Kunsthaus 1952, online <emuseum.ch>.

Secondary literature on FLW’s international travelling exhibition 1948-1956:

- Canali, Ferruccio : « La Mostra di Frank Lloyd Wright a Firenze. 1951 (parte 1). L’epistolario Ragghianti-Zevi e Wright», Bollettino della società di studi fiorentini 18-19/2009-2010, 162-177 online <https://www.academia.edu/10057312/La_Mostra_di_Frank_Lloyd_Wright_a_Firenze_1951_parte_1_Lepistolario_Ragghianti_Zevi_e_Wright>

- Canali, Ferruccio : « 1951: ‘Frank Lloyd Wright: sixty years of living architecture’, le complesse vicende per l’organizzazione di ‘questa importante Mostra per l’italia’ e il contributo di Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti, di Oskar Stonorov e di Edoardo Detti », Bollettino della società di studi fiorentini 21/2012, 52-88 online <https://www.academia.edu/10057108/La_mostra_di_Frank_Lloyd_Wright_a_Firenze_1951_parte_2_Lorganizzazione_>

- Carotti, Lisa : I maestri dell’architettura moderna in mostra a Palazzo Strozzi : Wright, Le Corbusier e Aalto : riflessi nella Scuola fiorentina, Università degli studi di Firenze : Dipartimento di architettura, 2014 (dottorato di ricerca in progettazione architettonica urbana, Anni 2011-2013) online https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/301567348.pdf.

- Smith, Kathryn, Wright on Exhibit : Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Exhibitions. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

Building history of the Zurich Kunsthaus:

- Jehle-Schulte Strathaus, Ulrike. Das Zürcher Kunsthaus, ein Museumsbau von Karl Moser. Basel : Birkhäuser Verlag, 1982.

- Jehle-Schulte Strathaus, Ulrike, « Das Zürcher Kunsthaus, ein Museumsbau von Karl Moser », Werk, Bauen + Wohnen 70 (1983) Heft 5, S. 41-47, online <http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-53479>.

Photojournalism in Switzerland :

- Binder, Walter ; Bonnard Yersin, Pascale ; Yersin, Jean-Marc: « Fotografie », in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version as of 20.08.2020. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/011171/2020-08-20/, consulted on 10.08.2022.

- Bollinger, Ernst: « Illustrierte », in: Historisches Lexikon der Schweiz (HLS), Version as of 14.09.2011. Online: https://hls-dhs-dss.ch/de/articles/010471/2011-09-14/, consulted on 10.08.2022.

Sigfried Giedion’s mediation work in favour of FLW’s architectural position:

- Giedion, Sigfried. Space, Time and Architecture : the Growth of a New Tradition. Cambridge: The Harvard University Press, 1941

- Giedion, Sigfried. Architektur und Gemeinschaft : Tagebuch einer Entwicklung. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1956 (Engl. Architecture, You and Me : the Diary of a Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1958).

- Giedion, Sigfried, « Frank Lloyd Wright – Amerikaner und Individualist », Sie und Er, 31 Januar 1952, S. 16-17.

Americanism in Europe 18th-20th century:

- Damisch, Hubert ; Cohen, Jean-Louis. Américanisme et modernité : l’idéal américain dans l’architecture, Paris: EHESS, 1993 (especially von Moos, Stanislaus, « Sigfried Giedion ou la deuxième découverte de l’Amérique », S. 239-248).

- Kunz, Gerold, « Zieht hinaus! : Der Kalte Krieg und die Zersiederlung der Schweiz », Heimatschutz = Patrimoine 105 (2010) 4, S. 14-16, online <http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-176361>.

FLWs Foundation :

- https://franklloydwright.org

FLW’s architectural models at the Museum of Modern Art, New York:

- Broadacre City : < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/161773 >

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum : < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/161782>

- Mark’s Tower : < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/161770 >

- The San Francisco Call Building : < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/161768 >

- Davidson Little Farms Unit Project : < https://www.moma.org/collection/works/161772 >

FLWs Antiurbanism :

- Levine, Neil, Neil Levine, and Frank Lloyd Wright. The Urbanism of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Maumi, Catherine : Usonia ou le mythe de la ville-nature américaine, Paris : Editions de la Villette, 2008

FLWs Individualism :

- Johnson, Donald Leslie. The Fountainheads : Wright, Rand, the FBI and Hollywood. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2005.

FLW and fashion:

- Quinan, Jack, « Architect of an Image », The Whirling Arrow – News and updates from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation März 2018 online <https://franklloydwright.org/architect-of-an-image/ >.

- Gorman, Carma R., « Fitting Rooms: The Dress Designs of Frank Lloyd Wright », Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 30, No. 4 (Winter, 1995), pp. 259-277 online : < http://www.jstor.org/stable/4618516 >

- Andrew Bolton (curator), « In America: An Anthology of Fashion », Ausstellung im Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 7. Mai – 5. September 2022, website <https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2022/in-america-anthology>

- Sporn, Stephanie, « See The Met’s Latest Exhibition, Which Boldly Mixes Fashion and Frank Lloyd Wright », ADPRO (Architectural Digest) 4. Mai 2022, online <https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/see-the-mets-latest-exhibition-which-boldly-mixes-fashion-and-frank-lloyd-wright>.

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Hilla Rebay :

- « Zeitgenössische Kunst und Kunstpflege in U.S.A : Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation », Ausstellungskatalog, Zürich: Kunsthaus, 1947, online <https://digital.kunsthaus.ch/viewer/fullscreen/44322/1/>.

- Faltin, Sigrid. Die Baroness und das Guggenheim : Hilla von Rebay, eine deutsche Künstlerin in New York. Lengwil: Libelle, 2005.

- Levine, Neil, The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press, 1996.

Terminology and semiotics of fashion:

- Bieger, Laura. Mode : ein kulturwissenschaftlicher Grundriss. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 2012 (insbesondere Lehmann, Ulrich, « Mode gegen Moderne », S. 23-56).

- Bosc, Alexandra. Les années 50 : la mode en France, 1947-1957, Ausstellungskatalog, Paris: Paris Musées, 2014.

- Clancy, Deirdre. Costume Since 1945 : Couture, Street Style and Anti-Fashion. New York: Drama Publishers, 1996.

- Garagerocker, Romano, « L’histoire de la chemise à carreaux », Blog post 22 April 2022, Comme un camion online <https://www.commeuncamion.com/2014/03/05/lhistoire-de-la-chemise-a-carreaux/>.

- George, Sophie, Guérin, Caroline. Le vêtement de A à Z : encyclopédie thématique de la mode et du textile. Paris: Falbalas, 2010.

- Harvey, John Robert. Men in Black. London: Reaktion Books, 1995.

- Loschek, Ingrid. Reclams Mode- und Kostümlexikon. 6th, revised and updated edition, edited by Gundula Wolter. Stuttgart: P. Reclam jun., 2011.

- Remaury, Bruno ed.. Dictionnaire de la mode au XXe siècle. Paris: Ed. du Regard, 1996.

- Roetzel, Bernhard ; Beer, Günter. Der Gentleman : Das Standardwerk der klassischen Herrenmode. Rheinbreitbach: Ullmann, 2021.

- Rothenhäusler, Paul ; Küng, Edgar. Das kleine Kleiderbuch für die Dame und für den Herrn. Zürich: Sanssouci, 1960.

- Wenrich, Rainer Hg.. Die Medialität der Mode : Kleidung als kulturelle Praxis. Perspektiven für eine Modewissenschaft. Bielefeld : transcript Verlag, 2015 (especially Lehmann, Ulrich, « Der kalte Krieg im Anzug. Cary Grants Kleidung in Alfred Hitchcocks Der unsichtbare Dritte », S. 291-314).

Acknowledgement

I am extremely grateful to the following colleagues for their valuable tips and help with the present study: Dorothee Huber, Jacques Gubler, Basel, Almut Grunewald, Joya Indermühle, Sabine Flaschberger, Daniel Weiss, Bruno Maurer, Stanislaus von Moos, Zurich, Adelheid Rasche, Berlin, Thomas Rosemann.