There probably is nothing more mundane than idly flicking through a magazine on a Sunday afternoon. More often than not, fresh, grinning faces beam back at the reader as colourful page upon colourful page invites you to keep reading. That’s how it is today – and how it has been for ages.

When Andy Warhol (1928-1987) came to New York after graduating from university in 1949, drawing was an essential part of his daily routine in the early years. On the lookout for suitable motifs for his numerous advertising jobs, he was inspired by the nascent magazine culture and its visual language. The majority of the subjects of his early drawings on display in the exhibition “Andy Warhol – The LIFE Years 1949–1959” at ETH Zurich’s Graphische Sammlung, can clearly be traced back to images which the artist particularly discovered in the legendary American magazine LIFE – a trendy, colourful treasure trove of pictures that knew just how to reflect seductive modern life. From this rich stock of images, the passionate voyeur not only drew his very first inspiration, but also his artistic vocabulary – he managed to intensify the impact of his own visual language by specifically reducing and transforming the templates.

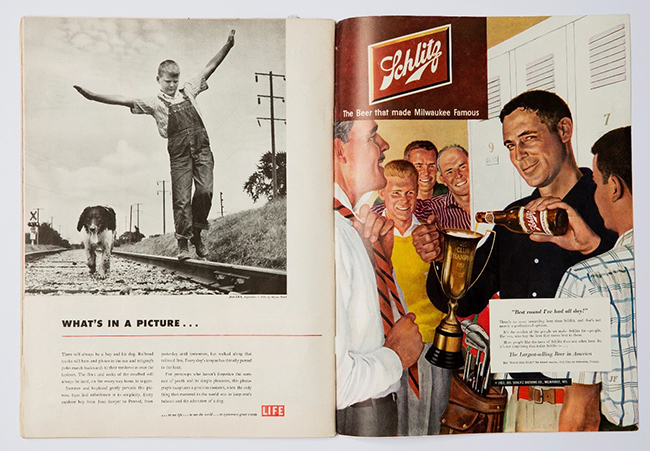

The following example just goes to show how this came about. So we join Andy Warhol and plunge into the LIFE issue from 23 July 1951, which cost readers 20 cents from the countless news stands at the time.[1] Leafing through it, you are immediately struck by the seeming abundance and confidence in the land of endless opportunities. The issue touts everything from the latest household gadgets, all manner of cosmetic products and especially fashionable food and drink to exciting films, hip restaurants and other entertainment venues – the leisure society is emerging, the middle class is becoming stronger. Page after page, the magazine alternates between adverts and researched reports. Until you eventually reach one of the last pages in the issue: it features a photo of a boy on the train tracks with outstretched arms (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: LIFE, 23 July 1951, pp. 108/109 (cf. also: http://tinyurl.com/jhcn9yk, status 10.12.2015)

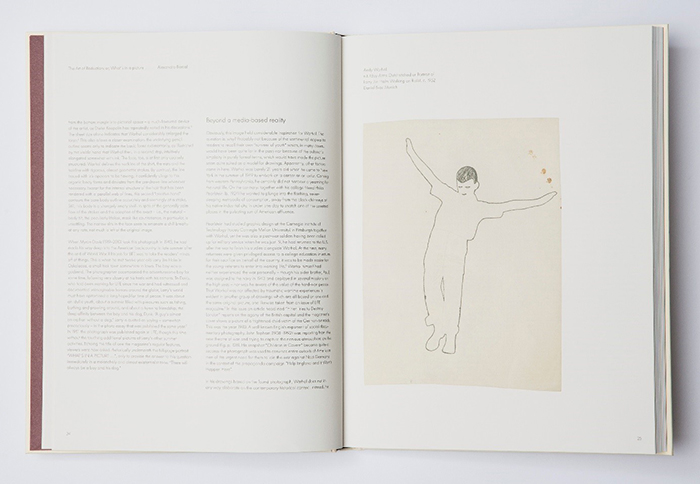

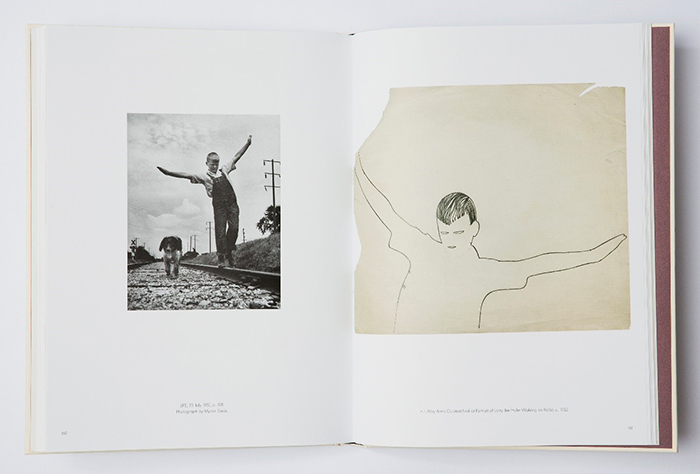

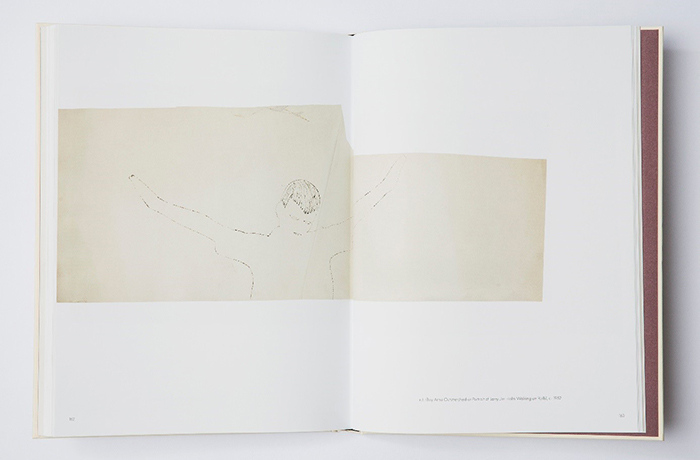

Concentrating on his feet, he is balancing along on a humid Midwest afternoon. Accompanied by his faithful dog, he simply seems to be idling away the time. No more, no less. Warhol must also have lingered on this remarkably unremarkable picture while trawling through the magazine on the lookout for suitable source material. Indeed, he selected this simple scene for his studies and adopted the significant silhouette of the boy for a series of sketches. In these, he seems to always have proceeded from a tried-and-tested principle: initially, he evidently traced the particular section of the picture on paper in pencil before outlining it in black ink. Whereas in one version Warhol outlined the entire figure on paper one-to-one (Fig. 2), in the second he left off the legs, only the tottering torso rising into the picture from the bottom of the page (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2: Centrefold from the catalogue for the exhibition “ANDY WARHOL – THE LIFE YEARS 1949-1959” (Hirmer 2015, pp. 24/25)

Fig. 3: Centrefold from the catalogue for the exhibition “ANDY WARHOL – THE LIFE YEARS 1949-1959” (Hirmer 2015, pp. 160/161)

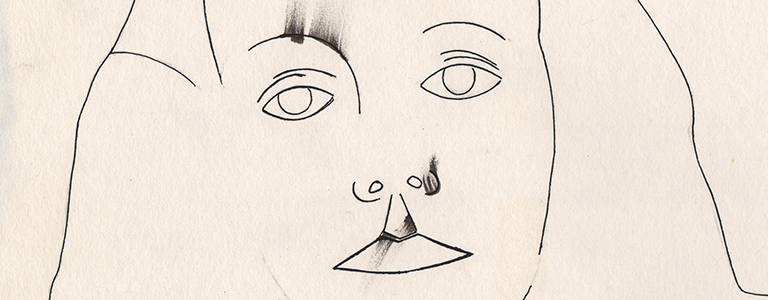

It is clear from the sheet size that Warhol magnified the torso considerably.[2] This enables a detailed consideration: the underlying pencil outline seems to merely hint at the basic forms – such as the visible hand, which Warhol then somewhat elongated intuitively with the ink. The face is also given only a rough initial structuring: Warhol defined the open shirt, ears and hairline with rigid, almost geometric strokes. The line drawn in ink looks fluid in comparison; it masterfully cradles the organic forms, departing from the sketched line where necessary. Apart from the internal structure of the hair created with a network of parallel lines, this second “creative” hand outlines the rough body accurately and ostensibly in one stroke. However, it is an oddly empty shell: despite the generally calm style, the curiously lifeless, mask-like facial expression particularly jars against the adoption of the exact, i.e. natural body angle. A cold breath seems to flow from the narrow slits in the face – at any rate, not much is left from the original picture.

When the American photographer Myron Davis (1919-2010) took this photograph in 1945, he was deep in the American hinterlands: for LIFE, he was supposed to take readers’ minds off things in the late summer following the end of the Second World War. And there, in Oskaloosa, a small village somewhere in Iowa, he met twelve-year-old Larry Jim Holm. It was a gift from above. The photographer accompanied the adventurous boy for a while, his camera ever at the ready. For Davis, who had been working for the agency since the war and seen and documented unimaginable horrors all over the globe, Larry’s world must have represented the epitome of a long-awaited peaceful existence. It was an idyllic youth, a summer full of pleasures such as fishing, bathing and hanging around – and an ode to friendship, the deep bond between the boy and his dog Dunk: “A guy’s almost an orphan without a dog,” as Larry was quoted as saying somewhat precociously in the documentary published the same year[3]. In 1951 the same photo was re-published in LIFE, albeit without the touching picture attachment of Larry’s other summer activities. “What’s in a picture…” – in accordance with the title of the magazine’s rubric – is now the rhetorical question posed underneath the full-page portrait before immediately answering in a melancholy, almost existential tone: “There will always be a boy and his dog.”

Fig. 4: Centrefold from the catalogue for the exhibition “ANDY WARHOL – THE LIFE YEARS 1949-1959” (Hirmer 2015, pp. 162/163)

Evidently, this image offered plenty of inspiration for Warhol. Why might this have been? Probably not because of the sentimental appeal of recalling one’s own “summer of youth”, which is usually somewhat longer ago; nor the purely formal simplicity of the subject matter, which makes it seem more than suitable for use as a template. Other factors can be inferred here. The boy, who is teetering along the tracks with his arms raised heading towards an uncertain destination, must have symbolised something of Warhol’s own inner fire. For him, the keywords in the text such as “summer and boyhood”, “boy walked alone” or “simple pleasures” must have had a real signal effect. Was it ties to his own person that played a key role in this early phase? The solitary childhood, the lifelong yearning for love and recognition, the sorrowful beauty of a man child? The smudged areas around the eyes in the third version of the motif using what is known as the “blotted line” technique (Fig. 4) and the upper body with arms stretched out above his head in particular are instinctively reminiscent of a Man of Sorrows, as the priest used to show him during Lent in the Orthodox Christian church St. John Chrysostomus in Pittsburgh – Warhol’s family was deeply religious. The seemingly naked body, the eyes closed in suffering, even the entire posture also almost evokes St. Sebastian as the patron saint of homosexuals – perhaps a nod to the artist’s sexuality and the otherness he sensed so intensely throughout his life. At any rate, as is so often the case, the distancing yet intensifying effect of Warhol’s adaptations oscillates here. The photo from the magazine seems present – and yet the template appears concealed. But as we have known since Michelangelo Antonioni, behind every image revealed there is another that in turn conceals another…[4]

Exhibition info:

ANDY WARHOL – THE LIFE YEARS 1949-1959

Graphische Sammlung ETH Zürich

4 November – 23 December 2015; 4 January – 17 January 2016

The exhibition presented an impressive group of around 80 drawings from Warhol’s early years: outstanding examples eloquently demonstrate the copying technique he developed, known as “blotted line”. Above all, however – and sometimes for the very first time – the drawings are compared to the magazines, the primary sources for the templates.

Catalogue info:

The following publication was published by the Graphische Sammlung ETH Zurich to coincide with the exhibition (German/English): ANDY WARHOL – THE LIFE YEARS 1949-1959, with texts by Alexandra Barcal, Olaf Kunde and Paul Tanner, Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2015; 196 pages, 116 illustrations, CHF 35 (exhibition price) / EUR 34.90 (in book shops), ISBN 978-3-7774-2438-5.

Works mentioned:

Fig. 2:

Andy Warhol

Untitled (Boy Arms Outstretched or Portrait of Larry Jim Holm Walking on Rails), c. 1952

Pencil and ink on paper

24.8 x 18.2 cm

Daniel Blau München

Fig. 3:

Andy Warhol

Untitled (Boy Arms Outstretched or Portrait of Larry Jim Holm Walking on Rails), c. 1952

Pencil and ink on paper

35.3 x 42.6 cm

Daniel Blau München

Fig. 4:

Andy Warhol

Untitled (Boy Arms Outstretched or Portrait of Larry Jim Holm Walking on Rails), c. 1952

Ink on paper

28 x 72.4 cm

Daniel Blau München

[1] Thanks to a collaboration between the US media group Time Warner and the search engine service provider Google, around 10 million photographs from the holdings of the former photo magazine LIFE have been uploaded onto the internet since 2008. All the issues published can even be browsed on Google Books; the aforementioned 23 July 1951 issue of LIFE can be accessed via the following link: http://tinyurl.com/ycffwngm (status 10.10.2015)

[2] We know from diverse sources that Warhol preferred to work with a light projector, such as through Ted Carey’s statement in an interview with Patrick Smith on 13 November 1978: “Warhol had an opaque projector […] and Warhol often used pictures that appeared in LIFE magazine.” In: Patrick Smith, Andy Warhol’s Art and Films, Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1986, S. 265.

[3] cf. LIFE, 3 September 1945, p.14: http://tinyurl.com/yc5pu7yn (status 10.12.2015)

[4] The full quote: “We know that behind every image revealed there is another image more faithful to reality, and in the back of that image there is another, and yet another behind the last one, and so on, up to the true image of the absolute, mysterious reality that no-one will ever see.” This is the final sentence spoken by the narrator in Antonioni’s last film Jenseits der Wolken, which he made in 1994 with the help of Wim Wenders.